Introduction to Film Studies 2: Narrative Structure

Introduction to Film Studies Lesson 2: Narrative Structure

Part of the Introduction to Film Studies course.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️

The Art of Time Travel

Prerequisite: Lesson 1: The Critical Faculty

Introduction: The Viewer as Detective

If Lesson 1 was about Space (what is in the frame), Lesson 2 is about Time.

When we watch a film, we often assume we are simply being told a story. We sit back, eat our popcorn, and let the events wash over us in a passive wave. But the "Critical Faculty" reveals that something far more complex is happening. The director is not just showing you events; they are withholding them, scrambling them, and stretching them.

A film does not download a complete narrative into your brain; it gives you fragments of a puzzle, and it is your job to assemble them. You are not a spectator; you are a detective. In this lesson, we look at the mechanic’s toolkit for manipulating time and information: Narrative Structure.

1. The Core Distinction: Story vs. Plot

The most fundamental distinction in film theory - and the one that confuses students the most - is the difference between the Story and the Plot. In casual conversation, these words are interchangeable. But to the critic, they are opposing forces.

The Story (The Mental Construct)

The Story is the complete chain of events in chronological order. It includes everything that happens to the characters, even the things we never see on screen.

- Example: In a detective movie, the "Story" begins when the murderer is born, continues through their childhood trauma, leads to the murder itself, and ends with the detective catching them. The Story exists only in your head—it is the mental timeline you build.

- Diegesis: We call the total world of the story action the Diegesis. Everything that belongs to the characters' world (the rain, the gun, the dialogue) is diegetic.

The Plot (The Physical Artifact)

The Plot is strictly what happens on screen, in the order the director chooses to show it. It includes Non-Diegetic material that the characters cannot perceive, such as the opening credits or the orchestral score.

- Example: The "Plot" of that same detective movie might begin with the dead body (The Middle of the Story), then flash back to the murder (The Beginning), and then jump to the trial (The End).

The Formula:

The viewer looks at the Plot to infer the Story.

Consider the famous literary definition by E.M. Forster: "The King died and then the Queen died." This is Story - simple chronology. But if we say, "The Queen died of grief because the King had died," that is Plot - it establishes causality. A filmmaker might complicate this further by showing us the Queen's funeral first, and then flashing back to the King's death to reveal the cause. In this case, the Plot is reversed, but the Story remains chronological.

2. The Engine: Causality and Motivation

Why do we keep watching? What drags us from one scene to the next? The engine is Causality.

Narrative is a chain of cause and effect. A gun fires (Cause) $\rightarrow$ A man falls (Effect). The filmmaker’s power often lies in breaking this chain to create intrigue.

- The Whodunit: We see the Effect (the dead body), but the Cause (the murderer) is withheld until the end.

- The Thriller: We see the Cause (a bomb placed under a table), but the Effect (the explosion) is delayed to create anxiety.

This leads to the principle of Motivation. In the real world, things happen randomly. You might trip on a sidewalk for no reason. In a movie, nothing is random. Every action must be motivated. If a character walks into a room, they must have a reason (to find a key, to hide, to kill). If the camera shows a close-up of a hammer in Act One, that hammer must be used in Act Three. This is known as Chekhov’s Gun: the promise that every element in the Plot serves a function in the Story.

3. The Flow of Information: Range of Narration

Once the plot is constructed, the director must decide how much information to give the viewer. This is the Range of Narration.

Omniscient Narration (Unrestricted)

The camera acts like a god; it knows more than the characters do. We might jump from one location to another, seeing the shark approaching the swimmer in Jaws long before the swimmer sees it.

- The Effect: Suspense. As Alfred Hitchcock famously argued, if you show the audience a bomb under the table, you create fifteen minutes of unbearable anxiety. If you don't show them, you only create fifteen seconds of surprise when it explodes.

Restricted Narration

The camera is tied to the knowledge of a single character. We only know what they know; we only see what they see. This is common in detective films like Chinatown or The Sixth Sense.

- The Effect: Mystery. Because we are trapped in the protagonist's perspective, we share their confusion and their fear. We cannot solve the mystery before they do.

4. Manipulating Time

Cinema is the only art form that can manipulate time as easily as space. We categorize this manipulation in three ways: Order, Duration, and Frequency.

Order (The Shuffle)

Life moves strictly forward. Film moves anywhere.

- Flashbacks (Analepsis): Jumping backward to explain a current motivation.

- Flashforwards (Prolepsis): Jumping forward to tease an outcome.

- Case Study: In Pulp Fiction, Quentin Tarantino scrambles the order of the scenes not to confuse us, but to highlight thematic connections rather than chronological ones. By showing us the character's redemption after we have already seen his death, the film forces us to focus on the morality of his choices rather than his survival.

Duration (The Stretch)

How long does an event take?

- Story Duration: The years covered by the narrative (e.g., Citizen Kane covers 70 years).

- Screen Duration: The running time of the movie (2 hours).

- Ellipsis: The most common tool of duration is the Ellipsis - simply cutting out the boring parts. We see a character get in a car, and then we cut to them arriving at work. We skip the 30-minute drive.

- Case Study: In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick uses a "match cut" (a bone thrown in the air turns into a spaceship) to compress millions of years of evolution into a split second of screen time.

Frequency (The Loop)

Usually, we see an event once. But sometimes, a Plot repeats a Story event.

- Case Study: In Rashomon (or The Last Duel), we see the same single event (a crime) played out multiple times from different perspectives. By manipulating frequency, the director challenges the very idea of objective truth.

The Philosophical Horizon: Constructivism and Phenomenology

Why does this matter for philosophy? Because it proves that Meaning is a Construction.

The Russian Formalists argued that a story does not exist in the text; it exists in the interaction between the text and the reader. This touches on Phenomenology—the philosophical study of how we experience consciousness.

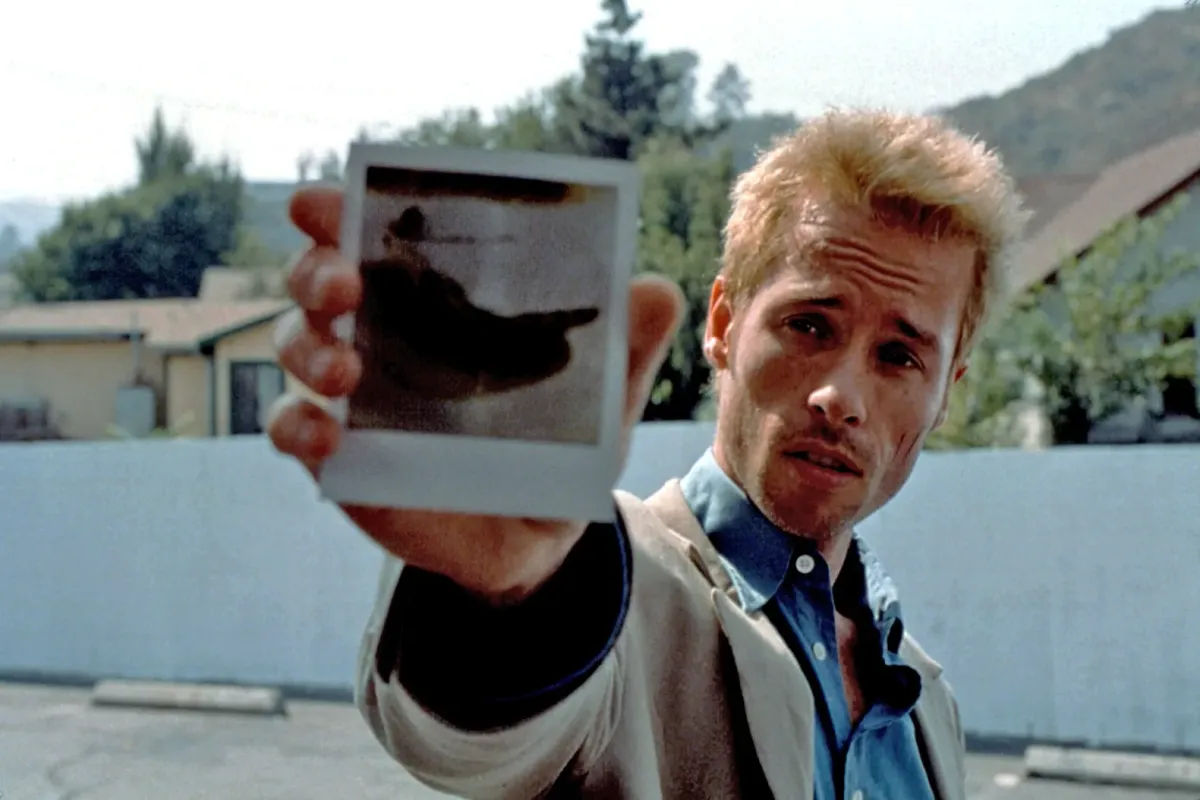

When you watch Memento, Christopher Nolan plays the Plot in reverse order. The protagonist, Lenny, has no short-term memory. By breaking the chronological Order, the Form forces you to share Lenny's disability. You don't know why you are running; you just know you are running.

You, the viewer, are doing the cognitive work that the protagonist cannot. You are holding the Story together in your mind while the Plot tries to tear it apart. This suggests that "Time" is not just something that happens to us; it is something we actively construct. We are the directors of our own consciousness, constantly editing our memories to make sense of the present.

The Seminar Room

Join the discussion below. (Note: You must be a logged-in member to comment.)

Today's Prompt: The Non-Linear Watch

Identify a film you have seen that manipulates Order (Flashbacks/Non-linear).

- The Film: (e.g., Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind).

- The Technique: Does it start at the end? Does it jump around?

- The Why: Why didn't the director just tell it straight? How did the scrambled structure change your feelings toward the character?

Continue the course

➡️ Next lesson: The Principles of Form

Discussion

Use the comments below to ask questions, raise objections, or test ideas from this lesson.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️