Introduction to Film Studies 6: Editing

Introduction to Film Studies Lesson 6: Editing

Part of the Introduction to Film Studies course.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️

The Invisible Art

Prerequisite: Lesson 5: Cinematography

Introduction: The Third Meaning

In the previous lessons, we discussed the "Raw Materials" of cinema – the script, the set, the lighting, and the camera. But none of this is actually "A Movie" yet. It is just a pile of footage.

Editing is the art of assembly. It is the only aspect of the filmmaking process that is unique to cinema. Photography has framing; theater has acting; literature has narrative. But only film cuts time into fragments and reassembles it to create a new reality.

The magic of editing lies in a phenomenon that the French critic Roland Barthes called the "Third Meaning." When you place Shot A next to Shot B, the audience does not just see two images; they see the relationship between them. They create a third idea in their mind that connects the two. This makes the Editor the true storyteller of the film.

1. The Kuleshov Effect: Context is King

To understand the psychology of editing, we must look to the 1920s Soviet Union. A filmmaker named Lev Kuleshov performed a famous experiment that changed film theory forever.

He took a static close-up of a famous actor, Ivan Mosjoukine, wearing a completely neutral expression. He then cut this same shot next to three different images:

- Face + Bowl of Soup ➡️ The audience raved about his performance: "He looks so hungry."

- Face + Dead Child in a Coffin ➡️ The audience wept: "He looks so devastated."

- Face + Woman on a Sofa ➡️ The audience gasped: "He looks so lustful."

The actor’s face never changed. The editing changed the audience's projection of his soul. This proves that in film, Context dictates Content. We do not judge a shot in isolation; we judge it by what comes before and after it. The editor does not just link scenes; they dictate the emotional truth of the performance.

2. The Two Schools: Continuity vs. Discontinuity

Broadly speaking, editors follow one of two opposing philosophies.

Continuity Editing (The Hollywood Style)

The goal here is Invisibility. The editor wants you to forget you are watching a movie. They want the story to flow seamlessly, so you focus on the narrative, not the technique.

To achieve this, they follow strict rules of logic, most notably the 180-Degree Rule. Imagine an invisible line connects two characters talking. The camera must stay on one side of that line. If the camera crosses the line, the characters will suddenly appear to flip positions (looking left, then suddenly looking right). This breaks the illusion and confuses the viewer's spatial map.

Discontinuity Editing (The Montage Style)

The goal here is Visibility. The editor wants you to feel the cut. They want to shock you or force you to think intellectually about the construction of the image.

- Jump Cuts: Cutting from the same angle with a slight time jump (made famous by Jean-Luc Godard in Breathless). It creates a jittery, anxious energy.

- Intellectual Montage: Cutting two unrelated images together to create a metaphor. In Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin cuts from a shot of sheep being herded to a shot of men rushing to a factory. He is saying "Workers are Sheep" without writing a word of dialogue.

3. Parallel Editing: The Cinema’s Superpower

Perhaps the most potent tool in the editor's kit is Cross-Cutting (or Parallel Editing). This is the act of cutting back and forth between two events happening in different locations at the same time.

In The Silence of the Lambs, the editor cuts between the FBI ringing a doorbell and the killer in a basement hearing a bell. We assume the FBI is at the killer's house. The tension builds. When the door opens to reveal the FBI is at the wrong house, we are shocked. The editor has manipulated space and time to create suspense, tricking us into believing a connection that didn't exist. This ability to manipulate "Simultaneity" is cinema's superpower—we can be in two places at once.

4. Rhythmic Relations: The Beat of the Film

Just as music has a tempo, film has a rhythm determined by the length of the shots.

- Fast Cutting: A series of shots lasting 1-2 seconds creates adrenaline, chaos, and confusion. This is the language of the Action movie (e.g., The Bourne Identity).

- Slow Cutting (The Long Take): A shot that lasts for minutes creates contemplation, realism, or uncomfortable tension. This is the language of the Art film (e.g., Tarkovsky or Cuarón).

A great editor acts like a drummer, speeding up the cuts during a fight scene to raise your heart rate, and slowing them down during a love scene to let you breathe.

The Philosophical Horizon: Dialectics

Why is editing philosophical? Because it is the visual application of Hegelian Dialectics.

The German philosopher Hegel argued that progress comes from conflict: a Thesis (Idea A) collides with an Antithesis (Conflicting Idea B) to create a Synthesis (New Truth C).

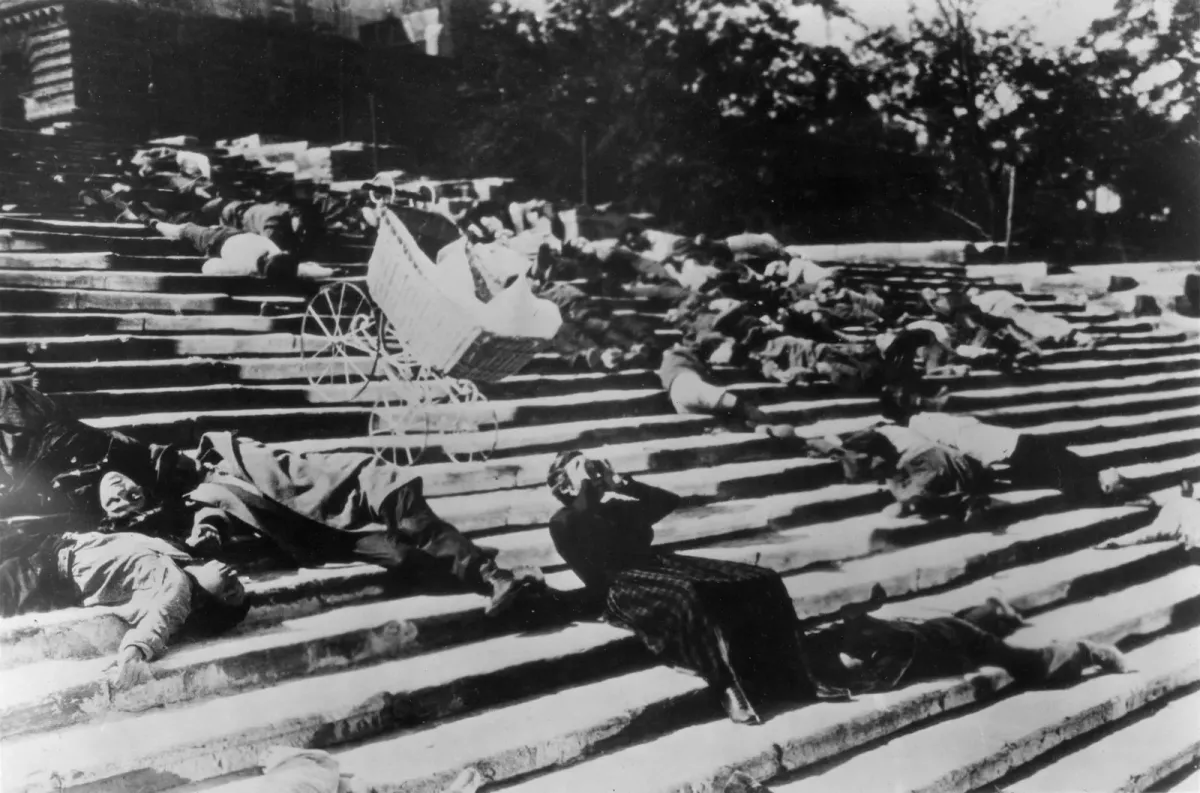

Sergei Eisenstein, the father of Soviet Montage, applied this directly to film structure. He didn't want shots to flow smoothly; he wanted them to collide.

- Shot A: The Boot crushing the hand.

- Shot B: The Baby carriage rolling down steps.

- Synthesis: The Viewer feels Outrage.

Eisenstein believed that smooth editing made the audience passive and sleepy. He believed that "Dialectical Editing" – editing based on conflict and shock – was the only way to wake the audience up and provoke revolutionary thinking. Editing teaches us that truth is not static; it is created through the violent collision of opposing forces.

The Seminar Room

Join the discussion below. (Note: You must be a logged-in member to comment.)

Today's Prompt: The Invisible vs. The Visible

- The Invisible: Find a scene where you didn't notice the editing at all. How did the director hide the cuts? (Look for "cutting on action"—cutting exactly when a character moves).

- The Visible: Find a scene where the editing made you feel uncomfortable or disoriented. Why did they break the rules?

Continue the course

➡️ Next lesson: Sound

Discussion

Use the comments below to ask questions, raise objections, or test ideas from this lesson.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️