Introduction to Film Studies 7: Sound

Introduction to Film Studies Lesson 7: Sound

Part of the Introduction to Film Studies course.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️

The Hidden Narrative

Introduction: The Forgotten Sense

We call it "watching" a movie, but we should call it "experiencing" a movie.

While the eyes are focused on the screen, the ears are being manipulated by a complex architecture of noise. Sound is often called the "Invisible Narrative." You can close your eyes and look away from a scary scene, but you cannot "close" your ears. This makes sound a more subconscious, visceral tool than the image. A horror movie is rarely scary on mute; the fear lives in the low-frequency hums and sudden stingers that bypass the intellect and strike the nervous system directly.

Despite this power, sound is often treated as an afterthought by viewers. In this lesson, we will dissect the three "stems" of the soundtrack – Dialogue, Effects, and Music – and analyze how they dictate our perception of reality.

1. The Source: Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic

The most fundamental distinction in sound theory is the source. Where is the sound coming from?

Diegetic Sound is any sound that originates from within the story world (the diegesis). If a character turns on a radio, slams a door, or speaks a line of dialogue, that is diegetic. The characters are aware of these sounds.

Non-Diegetic Sound is sound that originates from outside the story world. The most common example is the musical score. When a romantic violin swells during a kiss, the characters cannot hear it; only the audience can. It is a commentary on the action, not a part of the action.

However, great directors often blur this line to create psychological depth. In Apocalypse Now, the sound of helicopter blades (Diegetic) rhythmically morphs into the ceiling fan in the hotel room, and then into The Doors’ song "The End" (Non-Diegetic). This "Sound Bridge" tells us that the war is not just happening outside; it is happening inside the protagonist's mind. The soundscape collapses the distance between reality and memory.

2. Fidelity: The Lie of Realism

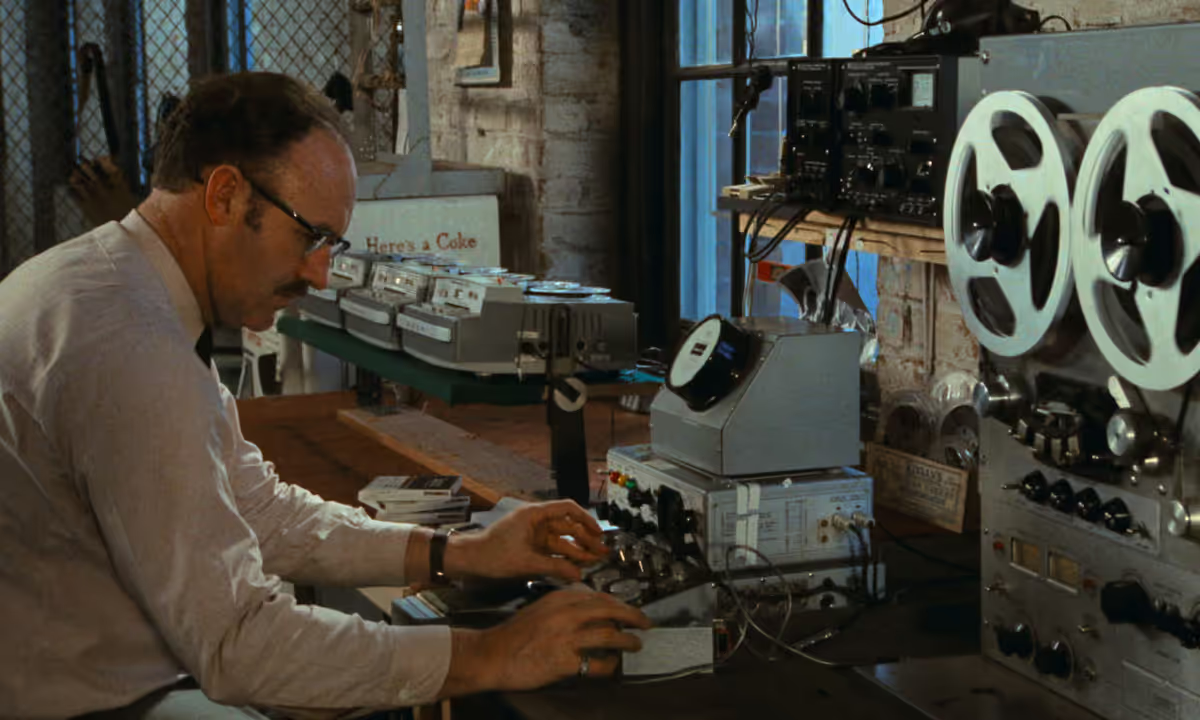

We tend to assume that the sound we hear in a film is the sound that was recorded on set. This is almost never true.

Cinema is an art of construction, not documentation. The microphones on a film set are designed to capture dialogue; they are terrible at capturing footsteps, punches, or rustling jackets. Those sounds are added later by Foley Artists, who work in studios smashing watermelons to simulate skulls cracking or rustling cornstarch to simulate walking in snow.

This leads to the concept of Fidelity: Does the sound match the source?

- High Fidelity: A dog opens its mouth and barks. This reinforces Realism.

- Low Fidelity: A dog opens its mouth and a human voice speaks. This breaks the illusion.

Comedy often relies on a breach of fidelity. In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the knights pretend to ride horses, but the sound is provided by squires banging coconuts together. The joke lies entirely in the gap between the visual reality (no horse) and the sonic reality (hoofbeats).

3. Mixing and Perspective

Just as the camera has a "perspective" (Long Shot vs. Close Up), sound has perspective too. The Sound Mixer decides how loud a sound is relative to others, and this hierarchy tells the audience what to pay attention to.

Consider the "Sonic Close-Up." In a busy nightclub scene, the background music might be deafening. But when the two lovers speak, the background noise unnaturally fades away, and their whispers become crystal clear. This is not realistic—in real life, they would be shouting—but it is emotionally true. The mix isolates them in a private bubble of intimacy.

Conversely, a director can use Subjective Sound to force us into a character's headspace. In Saving Private Ryan, when the shell explodes near Tom Hanks, the sound of the battle drops out completely, replaced by a high-pitched tinnitus ring. We are no longer observing the war; we are experiencing his physical trauma.

4. The Power of Silence

Silence is not the absence of sound; it is a specific sound choice.

In a medium defined by noise, silence is a weapon. It creates tension or emphasizes isolation. In No Country for Old Men, the Coen Brothers removed almost the entire musical score. The silence makes the violence feel raw, realistic, and uncomfortably intimate. We hear the killer’s breathing and the squeak of his boots, which is infinitely scarier than any orchestral swell.

The Philosophical Horizon: The Acousmêtre

Why does sound matter to philosophy? It brings us to the Ontology (the nature of being) of the film world.

The theorist Michel Chion coined the term Acousmêtre (Acoustic Being) to describe a character who is heard but not seen. Think of the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz, the Mother in Psycho, or HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Because these beings have no body, they cannot be touched or killed. They seem to be everywhere (omnipresent) and know everything (omniscient). They possess a god-like power over the narrative. In almost every story featuring an Acousmêtre, the climax involves finding the source of the voice. When the Wizard is revealed to be a frantic little man behind a curtain, he loses his power. The moment the voice is attached to a body (embodied), it becomes mortal. This teaches us a profound philosophical lesson about authority: power often relies on remaining invisible.

The Seminar Room

Join the discussion below. (Note: You must be a logged-in member to comment.)

Today's Prompt: The Sonic Detective Watch a scene from a favorite film and listen only to the Background Noise (Ambient Sound).

- The Film: (e.g., Blade Runner).

- The Sound: (e.g., The constant hum of neon lights and rain).

- The Analysis: How does this background noise change the mood? If the scene were silent, would the city feel as oppressive?

Continue the course

➡️ Next lesson: Auteur Theory

Discussion

Use the comments below to ask questions, raise objections, or test ideas from this lesson.

⬅️Previous Lesson | Course Syllabus | Next Lesson ➡️